Check valves are finnicky beasts. Their small flow coefficient compared to their nominal diameter often results in them being the most restrictive component in the system, and the cracking pressure can be deceptive in how we think about the valve’s operation. In this post, I will discuss a number of criteria to be considered in the selection of a check valve.

- Cracking Pressure

- Reseal Pressure

- Flow Coefficient

Cracking Pressure

Cracking pressure is one of the few things that is always specified for a check valve. It is always a toleranced value, and this tolerance might be more than you’d expect. For example, a Swagelok C series check valve with a nominal cracking pressure of 1/3 psi, the range is up to 3 psi. This would make this valve an unsuitable selection for a system which would nominally only have 2 or 3 psi difference between the upstream and downstream side of this valve.

Reseal Pressure

Reseal is the pressure differential at which a check valve closes. This value is sometimes not listed or well characterized by a manufacturer. It is important to understand the reseal behavior in systems which are intolerant to reverse flow across a check valve. Check valves with low cracking pressures often have a negative reseal pressure, that is, the pressure downstream of the check valve needs to be greater than the pressure upstream for the valve to close. Generally, a higher cracking pressure will result in a higher reseal pressure, and the cracking pressure is always larger than the reseal pressure.

Flow Coefficient

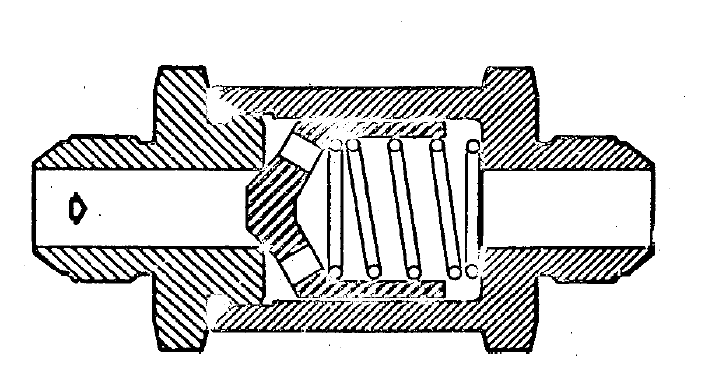

Check valve flow coefficients are generally low compared to their nominal size, although this is less true for swing-type check valves used in process water systems. This is usually of benefit to the check valve as it ensures that chattering behavior is less likely during nominal flows. Oversizing a check valve with a positive reseal pressure can lead to significant chatter and unsteady flows.

However, undersizing a check valve can lead to undesirable behavior as well. Large pressure drops and reduced system flow rates are obviously undesirable. If possible, it is best to size a check valve for an allowable pressure drop in excess of the selected cracking pressure at your nominal system flow rate. The tolerance of the selected cracking pressure should be taken into account, and the margin applied should be proportional to the cracking pressure.

Design examples

When considering a check valve application, it is important to ask the following questions:

- How much reverse flow is allowable?

- What is the allowable pressure drop for this valve?

- How much backpressure is this valve expected to experience?

Consider the case where a small amount of reverse flow is allowable, the valve is expected to experience significant backpressure at times, and the allowable pressure drop is minimal. In this case it would be beneficial to select a large check valve with a low cracking pressure, as resealing will occur when the backpressure is high. Compare this to an example where no reverse flow is allowable, minimal backpressure is expected, and the pressure drop across the valve is allowed to be moderate. In this situation it would be beneficial to select a check valve with a higher cracking pressure, a positive reseal pressure, and a smaller flow coefficient.

If you are having trouble with selecting the correct check valve for an application, reach out to me at [email protected]!